20/014

Ludivine Gragy

Landscape Architect

Berlin

«I imagine a future where landscape architecture becomes more confident and propose new visions with real ecological statements.»

«I imagine a future where landscape architecture becomes more confident and propose new visions with real ecological statements.»

«I imagine a future where landscape architecture becomes more confident and propose new visions with real ecological statements.»

«I imagine a future where landscape architecture becomes more confident and propose new visions with real ecological statements.»

«I imagine a future where landscape architecture becomes more confident and propose new visions with real ecological statements.»

Please, introduce yourself…

I am a landscape architect working since 2016 as an independent in Berlin. Field experiences in Japan and Switzerland have undeniably influenced my approach. Intuition on site often gives me impulse to the first steps of the design process. There is a necessity to capture the specificity of a given environment to enhance it through the project. Aside from to my own practice I also had the chance to work with atelier le balto for a number of years. Being a gardener and a landscape architect in parallel is an enriching working combination and one that I have learned from them; maintaining a permanent link between creation, construction and care comes naturally to me.

How did you find your way into the field of Landscape Architecture?

I grew up in Fontainebleau, a forest-land south of Paris. The rural landscape around me played an important role in my development and I learned about plants and their uses through my ground-rooted grandparents. At that time ethnobotany wasn’t a trend but a basic knowledge imparted from generation to generation in order to take advantage of plants and trees in the surrounding areas. As I always wanted to become an architect I first studied ‘design d’espace’ in applied art college where I had the chance to explore different mediums of expression. After finishing my design studies I had the intuition to pursue landscape architecture. I realised that this could merge my interest for spaces, botany and beings (human and non-human) into one practice.

What comes to your mind, when you think about your diploma project?

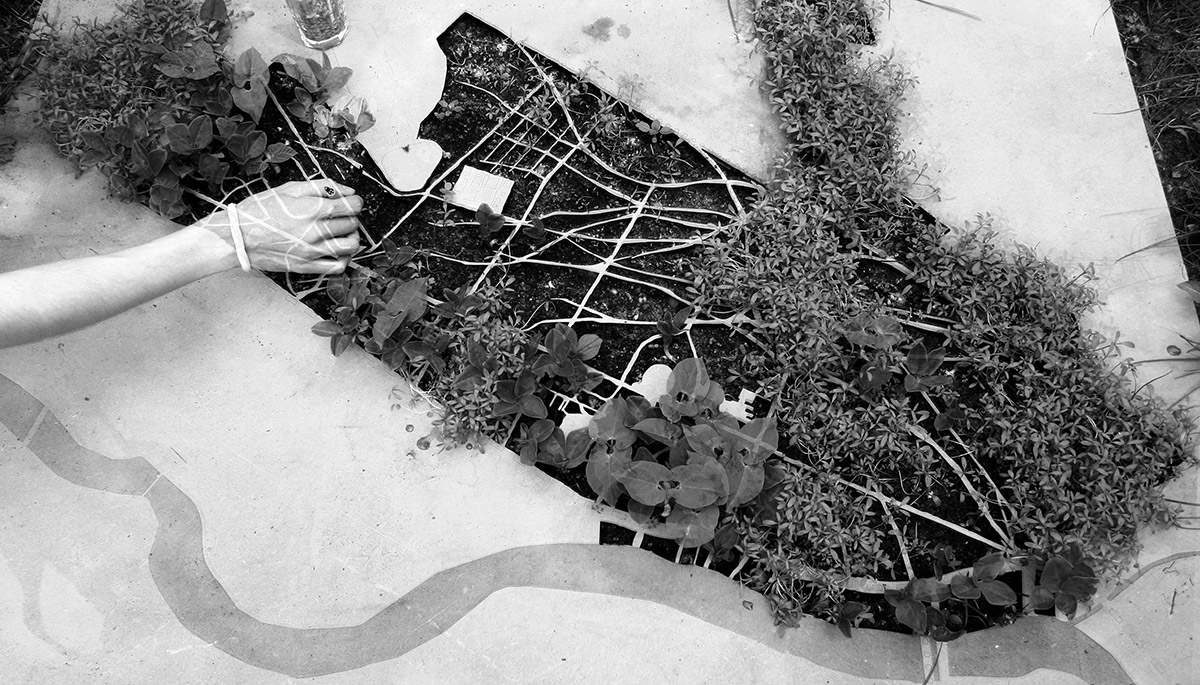

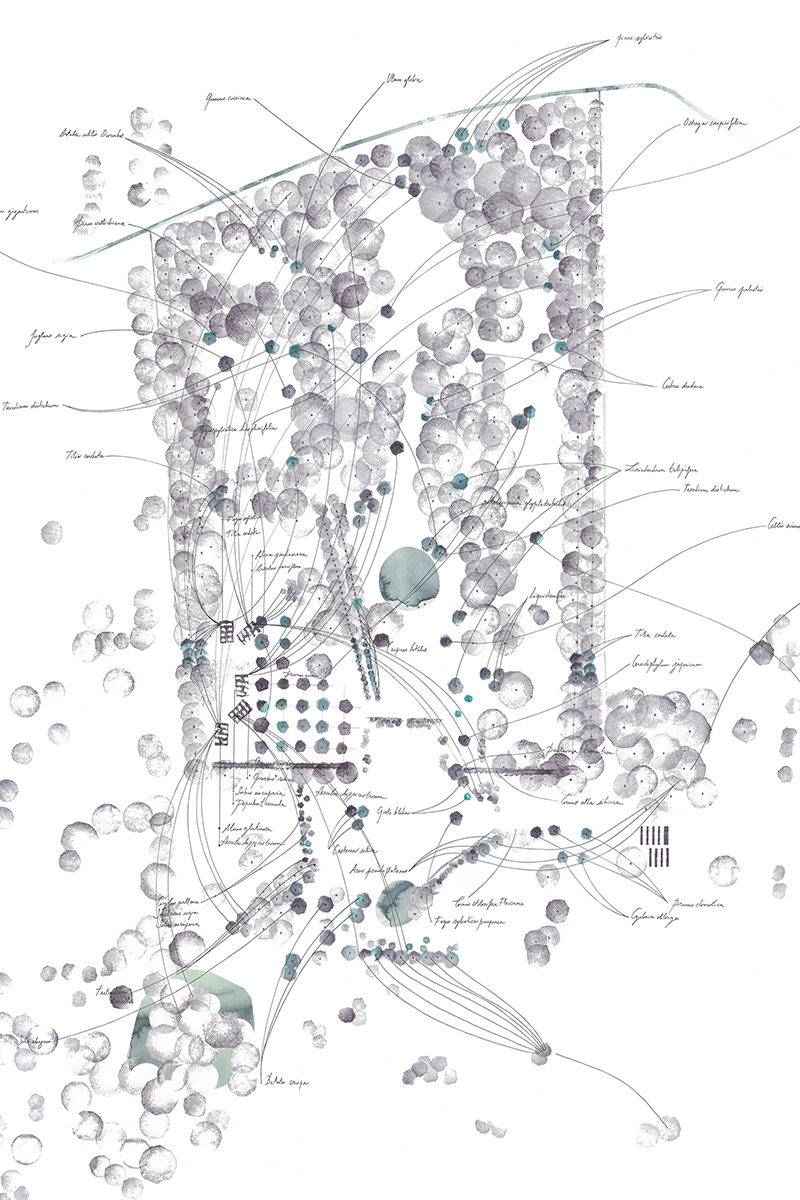

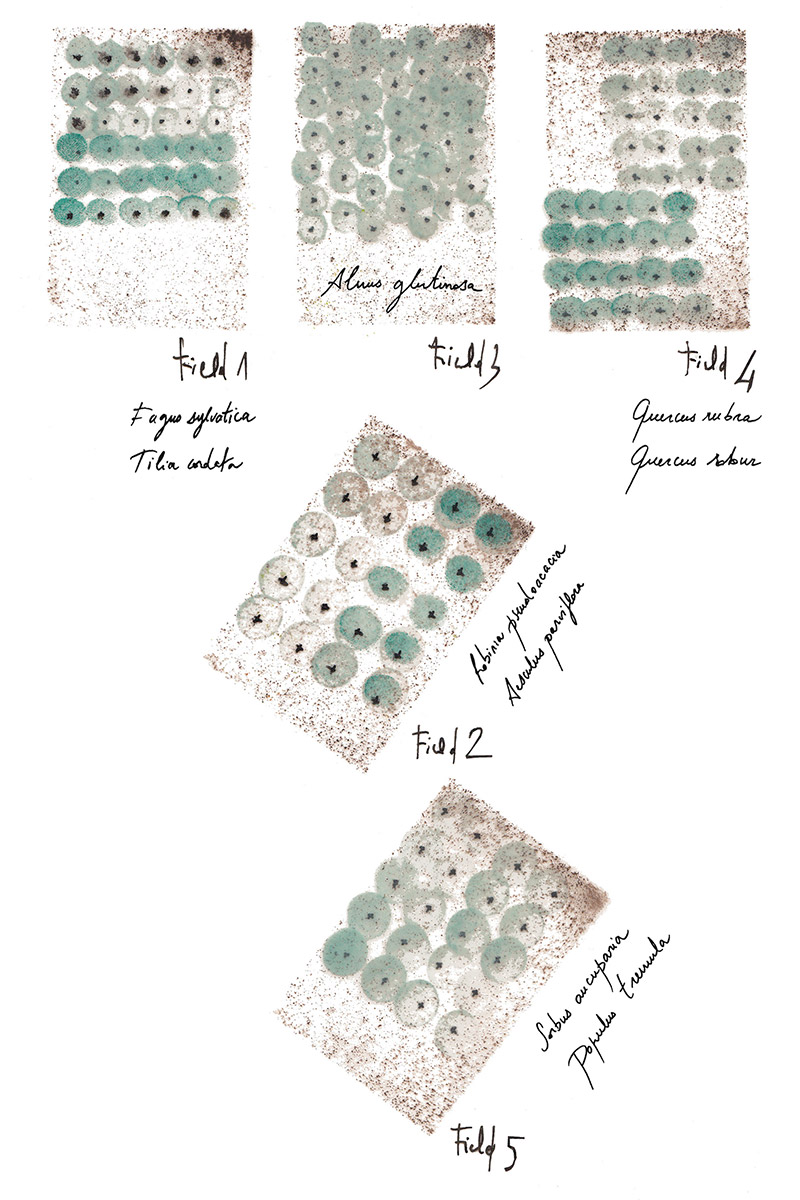

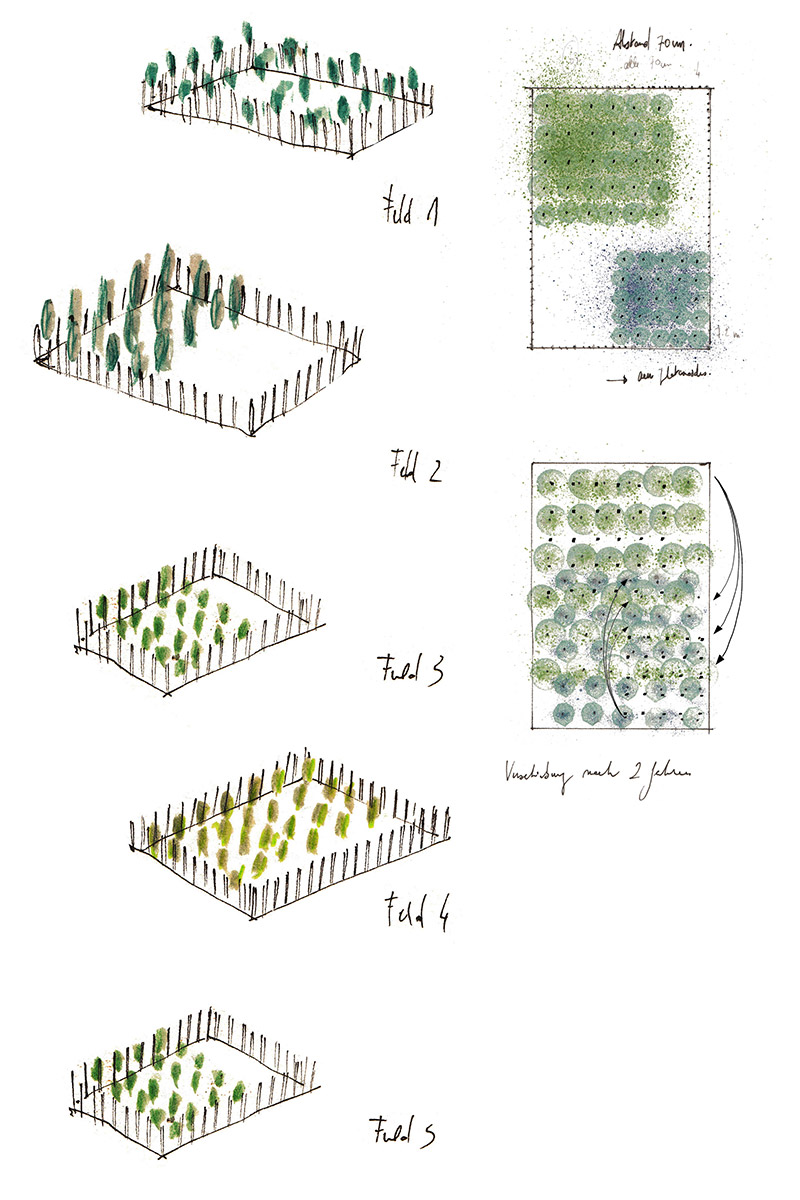

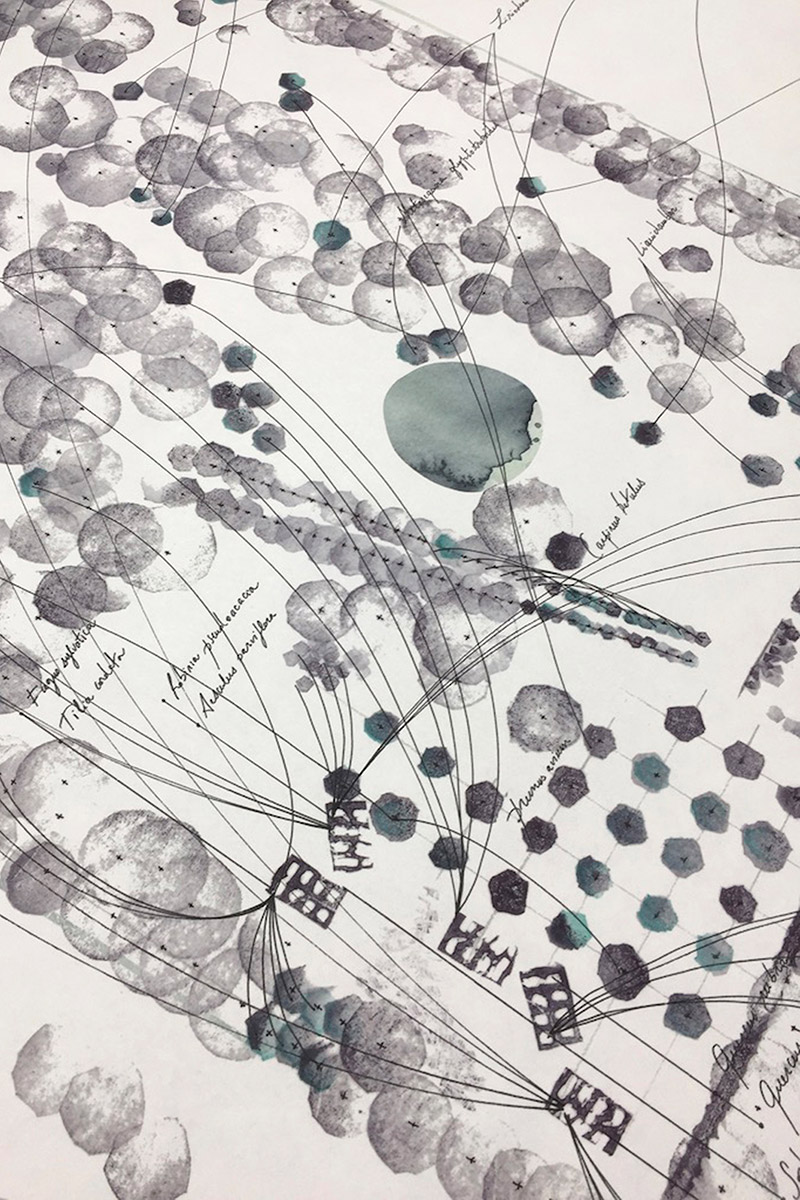

Confronted by the post GDR thematic when I discovered Berlin, I chose to dedicate the time of my diploma to explore the future potential of a dated forest-park on the east side of Berlin, Volkspark Wuhlheide. I first focused on the principle of sedimentation, exploring what could be done with the layers of historical information retained within the ground itself. Considering the ground as a fundamental component of a landscape architecture project and being frustrated by conventional representation, I had the idea to plant a living model in the soil. Sowing different seeds, each representing a species of tree and a stage of its forestial growth.

What are your experiences founding your Studio and working as a self- employed Landscape architect?

I started my own practice after winning a competition for a Swimming pool in Le Locle Switzerland. The project was put on hold because of monetary limitations but fortunately I managed to obtain other projects to continue. It was the push to jump into cold water. Working independently requires a lot of determination not to be forced to compromise too soon. Especially as a young office, it is important not to loose the guideline you have fixed for yourself by making projects you don’t believe in or identify with just in order to survive financially.

How would you characterize Berlin as a location for practicing Landscape Architecture? How is the context of this place influencing your work?

Berlin is a very liberating and stimulating context to work within. At first I was fascinated with its rough non-homogeneous cityscape due to its very recent history, the wide streets, the amount of parks and open spaces without any defined use. Berlin felt very freeing and as though it had the space to make it your own. Even though this situation has drastically changed in the past 10 years, the once empty spaces that were used to pioneer vegetation and transgressive behaviours have now been replaced by shopping malls and working centres with sterile outside spaces especially on the Spree riverbank or am Nordhafen where the strip of the wall used to be. I am a bit perplexed regarding the change happening right now and feel desolate seeing those open spaces essential for ecosystems and temperature regulation being filled up so fast. It makes me wonder the meaning of the restriction we face sometimes not being allowed to cut a tree down for ecological reasons while drastic changes happen in short periods of time turning huge pieces of lands into impermeable surfaces.

Today landscape architects and architects often form a partnership to enter competitions. How important is the relationship and a mutual understanding between you and the architect?

True but probably due to the lack of exchange during their studies, architects and landscape architects still look at each other with big fish eyes - (laugh). Even I am convinced that we have so much to learn from each other and that spaces growing out of a close collaboration from the very beginning of the design process have a lot of value.

What does your working space look like?

It is a light space with bright windows, high ceilings and plants from different origins. The workshop aspect of the space allows for the freedom to use materials like soil, pigment or concrete when working. I also like the connection to the street that it gives. The studio space used to be used to manufacture brass instruments and then was a shop that sold fur.

For you personally, what is the essence of architecture?

Finding the right proportions to make movement and uses intuitive. Combining the right materials to provoke sensations and surprise. Creating playful visual or physical dialogue with the surrounding landscape.

Whom would you call your mentor?

During my time in Japan, I worked alongside Michio Tase for several months; he is the person that I would most likely call a mentor. Despite our age and cultural differences we developed an implicit understanding and trust for each other. Japanese landscape architect, professor and botanist, he designed a modular and autonomous plantation system modelled for a metropolis like Tokyo where a direct connection to the ground may be missing. On a larger scale he planned a sustainable farm in the Iwate Prefecture of Japan. At that time, it was a pilot project for a tsunami disaster area, focusing on preserving the rural landscape and expanding it to reintroduces wild horses. No matter the scale of the project, the ecological value is for him the primary concern, reintroducing the once native vegetation back to their original habitat. Working alongside him allowed me to realise the necessity of our work and helped to understand from an outside perspective the complex relationship that the Japanese have towards nature. I believe there are few people with an unexplainable aura that can drive others with their vision for the world. He is one of those people.

Name…

A Book: Les lieux et la poussière, Roberto Peregalli ‘Places and Dust’ is an essay on ‘beauty and fragility of our perishable world’, the nostalgia that inhabits places when they get outdated. I kept this book in mind for the last projects I have been working on, having to evaluate how much ‘design’ is needed and how much should be left untouched.

A Person: Lina Bo Bardi. For the extremely high quality of the spaces she created, her drive as a female immigrant architect in 1950s Brazil, her statement in architecture combine to the naïve style of her drawings, her eclecticism and interest for indigenous art. While visiting Sao Paulo, I spent a lot of time at Sesc Pompeia, which is to me the most convincing example of conviviality within architecture, directly illustrating the social aspect it can provide. It was impressive to see how popular the place still is for all generations. I was inspired by the way the air circulates throughout the entire building, the porous nature of the brick walls facing out to the streets that in turn create this flow from interior to exterior. Through a combination of use of materials, influences and simplicity I consider her work to be timeless.

A Building: Teshima Art Museum in the Japanese Inland Sea. This is not because of the cast roof that is shaped like a landscape but because of the symbiosis between landscape, art, architecture and the natural elements. Before entering the museum, you walk along a circular path through the surrounding landscape, this builds the anticipation before entering the space. The building is dedicated to reveal a single discrete phenomena, the sight of water-droplets on the ground due to the micro-topography of the floor. To show the physicality of the water falling from the sky and into the semi-contained space is an incredibly poetic way to link a structure to its surroundings. When designing a landscape I always have to question the route of the rainwater, which is linked to the porosity of the flooring material used in order to make sure that water can permeate.

An architectural element: Within traditional Japanese building culture there is Doma, this is a hard compacted dirt floor at the entrance of a building that is used as a workshop or storage space. This rough and absorbent surface makes manifest a slowing of the transition between outdoors and indoors.

How do you communicate/present Landscape Architecture?

Landscape architecture is a relatively recent discipline, due to this it is often misunderstood and a little underrated. I like to speak about planning as a ‘cumulative process’ starting with an immersion on site, taking notes and drawing, being involved with your own body to feel spaces in order to make the correct decisions regarding plants and material. Not being able to control all parameters, the real challenge for the landscape architect is to create living systems rather than ornaments or design objects.

How do you imagine the future?

I imagine a future where landscape architecture becomes more confident and propose new visions with real ecological statements. The financial aspect should not play a big role, it is our responsibility to create habitable spaces where people, animals and plants find their place without the feeling of restriction. Our job is about defining a frame for cohabitation.

Your thoughts on Space and Society?

One of my ongoing projects, a study for the public square of the Monastery Mariastein in Switzerland makes me think about the sacred nature of public spaces. How can the landscape architecture project guide the visitor in their transition through profane and sacred spaces? If people talk only of mobility, does this mean that there is no longer open space for retirement or slowness in cities? This is probably the reason why I developed such a fascination with cemeteries, occupying both a dynamic relation to temporal isolation from the motion of the city. Alongside this they also have the ability to mirror the society that they belong to.

Project